I’ve decided to attempt a regular series of blog posts focused on language and the far right because, on the one hand, I think it might be useful for other people and, on the other hand, giving myself a regular publication schedule will, I think, help me to work through my own thoughts. So here goes.

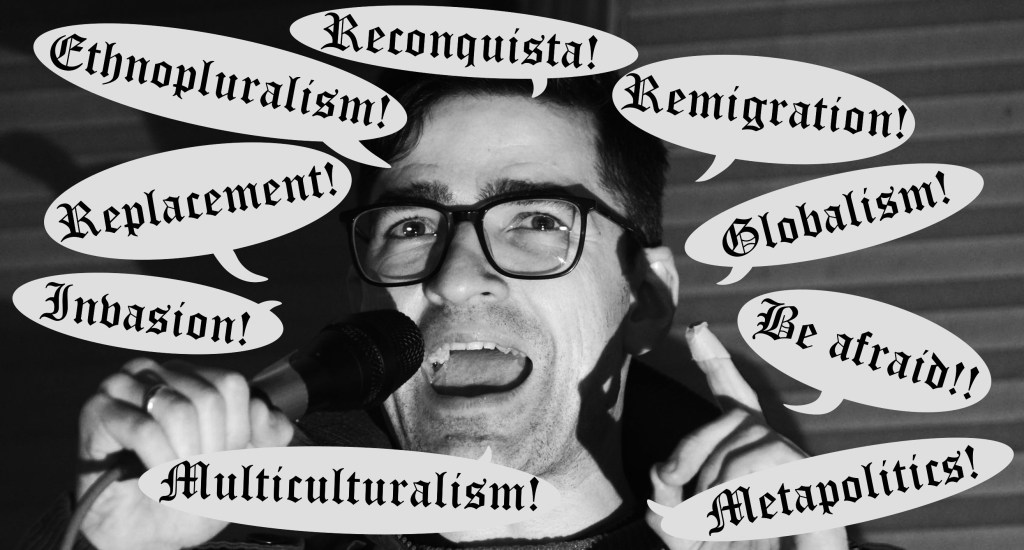

(Adapted from an original photo by Sebastian Willnow / picture alliance / dpa)

On Being a Witness to Fascist Language and Its Consequences

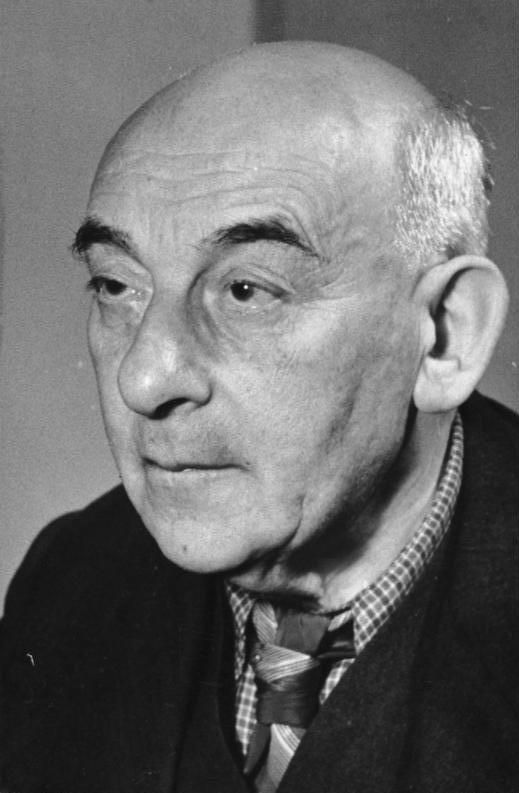

For the first post here, it seems only right and proper to start by discussing the first chapter of LTI, Victor Klemperer’s landmark 1947 book on the Nazi party’s use of language. Klemperer, a German-Jewish philologist who survived the Holocaust in large part (by his own telling) thanks to the support of his “Aryan” Protestant wife, kept a diary throughout the Nazi era. Being a word guy, he naturally kept track of what he called the Lingua Tertii Imperii (Language of the Third Reich, or LTI for short), and the book is based on the portions of his diary that dealt specifically with Nazi language. (The rest of his diaries have been published in various forms over the years, and at least some parts have been translated into English. I haven’t read the other volumes, but I’m told they offer an invaluable glimpse into daily life under Nazi rule, and I encourage people to read them. Scroll to the bottom for details.)

Chapter 1 of LTI addresses the parameters of what he considers to be “the language of the Third Reich,” which amounts to a rather broad spectrum. He begins by pointing to the variety of acronyms the Nazis used, noting that it was partly in response to (and as a parody of) the proliferation of Nazi acronyms that he privately coined the term “LTI” in the first place. Nonetheless, humor is in short supply in his description of its content. He writes

The Third Reich speaks with a dreadful uniformity from all its manifestations and remnants: from the exorbitant pomposity of its opulent buildings and from their ruins, from the soldiers and SA and SS men that it affixed on every kind of poster as idealized types, from its Autobahns and mass graves. All of that is the language of the Third Reich, and of course all of that is discussed in these pages. (Klemperer, 20)

Shortly thereafter, he also mentions “the language of shop windows, posters, brown uniforms, flags, arms extended in Nazi salutes, and pruned Hitler mustaches” (21). Language is never limited exclusively to verbal speech or written text, and that is particularly true of language that is meant to persuade, maintain the ideological orientation of the already persuaded, or remind dissenters of their own subordinate status.

This will probably not be surprising to most people, but Klemperer also notes the strict control that the regime exercised of the use of language, noting that

Everything that was printed and spoken in German was brought in line with official party norms; whatever somehow deviated from the one approved form did not go out; whether book or newspaper or official letters or agency forms – everything swam in the same brown sauce, and this absolute uniformity of written language is the basis for the consistency of all forms of speech. (22)

And with that, we come to what is arguably the most important point of this chapter, namely when Klemperer addresses the question of how Nazi language got into the heads of so many people.

What was Hitlerism’s most powerful means of propaganda? Was it individual speeches by Hitler and Goebbels and their remarks on this or that subject? Their incitement against Jewry? Against Bolshevism?

Certainly not, because much of it remained opaque to the masses or bored them through eternal repetition.

…

No, it was not individual speeches that had the strongest impact, nor was it articles or fliers, posters or flags. It was not achieved by means of anything that would have had to be internalized through conscious thought or conscious feeling.

Instead, Nazism eased its way into the flesh and blood of the crowd through individual words, turns of phrase, and sentence structures that it imposed through millions of repetitions and that were mechanically and unconsciously adopted. People often understand Schiller’s phrase “sophisticated language that writes literature and thinks for you” as saying something purely aesthetic and more or less harmless. A successful verse in “sophisticated language” proves nothing about the poetic powers of the person who wrote it; it is not particularly difficult to take on the air of a poet and thinker using highly cultivated language.

But language does not just write literature and think for me. It also increasingly guides my feelings and governs my entire spiritual being as it becomes more and more obvious to me, as I unconsciously give myself over to it. And if that sophisticated language is made up of poisonous elements or is used as a carrier for poisonous materials? Words can be like tiny doses of arsenic: they are swallowed without being noticed, they do not appear to have any impact, yet after a little bit of time, the poison takes effect. (25)

(Source: Bundesarchiv, Bild 183-16552-0002)

This passage, taken by itself, is admittedly reductive: all the repetition in the world could not have made Nazi ideology take root if the groundwork had not already been laid through, among other things, long-standing antisemitic sentiment, a burgeoning “race science” movement throughout Western civilization, a strictly gendered division of labor, and a deep-seated ideology of colonialism and white supremacy across much of Europe. However, at least in an immediate sense, it is not much of an overstatement to say that Nazi language (again, broadly conceived) and the party’s very extensive control over what and how language was used did a great deal to bring what might have been buried, latent ideas to the surface and activate them for a lot of people.

In Klemperer’s telling, part of the problem with the insidious effect of fascist language is that people often wind up using it (and perpetuating the ideas bound up with it) without even realizing where it came from, and they continue using it even when the regime has been vanquished, something Klemperer also briefly describes with respect to Germany in the years following the Nazi era. After noting frequent postwar discussions about eliminating the fascist mindset, executing war criminals, driving “little party members” (which he describes as “language of the Fourth Reich!”) out of official positions, removing nationalist books from circulation, renaming streets, etc., he points out that

The language of the Third Reich has been able to survive in certain characteristic expressions; they have eaten their way so deeply that they seem to be a permanent possession of the German language. Since May 1945, how many times have I heard in radio speeches, at passionately antifascist demonstrations, for example, talk of “characteristic” traits or the “militant” essence of democracy! These are expressions from the center – the Third Reich would say “from the Wesensmitte [central essence]” – of the LTI. (24-5)

Because of, as he notes, the way that language penetrates our thinking through endless repetition, he argues that it is not just pedantry to push back against its use.

But Is This Useful?

What does all this mean in 2025? A lot, I think.

I do want to be clear that the seemingly constant urge to compare all things authoritarian to Nazis brings quite a few problems along with it, not least of all the way that it tends to present fascism (or authoritarianism, or totalitarianism, or Nazism) as a problem of the past and (for those of us who don’t live in Germany) as something that “those people” did. It externalizes the problem and has a way of ridding those of us living in the twenty-first century and far from the territory of the former “Third Reich” of responsibility for addressing related problems in the here and now.

It also raises the disturbing prospect of potentially comparing one group’s suffering to another’s, and there is very little to be gained from that.

Nonetheless, this doesn’t mean that we can’t extrapolate some principles from analyses of Nazism, Italian fascism, Francoism, etc., that apply to reactionary authoritarianism more generally. In the present case, Klemperer’s understanding of the “Language of the Third Reich” as something that became ubiquitous – not limited only to official speeches or party newspapers – and the way that it infiltrated people’s minds through endless repetition and normalization clearly apply in present-day situations.

(Source: Maranie R. Staab, AFP via Getty Images)

Looking first at “language” as it exists beyond spoken or written communication, we’ve seen in recent years how, for example, the Proud Boys adopted black Fred Perry polo shirts with yellow trim (despite the company’s unequivocal rejection of any affiliation) as a uniform, turning them into symbols of their own group cohesion and an extremely aggressive form of “Western” nationalism. In fact, it is difficult to accept the resounding echo of the black shirts worn by Mussolini’s squadristi as entirely coincidental. The historical parallels are not precise, but if anything, it appears retrospectively to be an aspirational gesture on the part of the Proud Boys, who were increasingly becoming a paramilitary organization on behalf of the Republican party toward the end of Donald Trump’s first term as president.

The use of the “OK” hand gesture will likely warrant an entire post of its own at some point in the future, but suffice to say, for decades it was an innocuous signal in the US (and likely in other places as well, where it wasn’t understood as an offensive representation of something else entirely) meaning something along the lines of “I understand” or “No problem.” Through a series of initial overreactions to its neutral use by a few people who happened to be associated with the far right, right-wing actors broadly adopted it, in part as a way of making fun of the people who had misinterpreted it. By now it is claimed by a variety of different far-right figures who don’t otherwise necessarily agree on ideology or even like each other. But in any event, it has clearly taken on a meaning that ranges from support for authoritarianism to outright approval of deadly acts of terror.

With respect to language in the more conventional sense, it is not by accident, for instance, that European “identitarians” have been throwing around the term “remigration” (their own coinage) at every opportunity over the past several years. It is a term that sounds relatively harmless until you start to think about its broader implications: they are talking about sending people who are in Europe and have non-European backgrounds “back” to the countries they or their ancestors came from (regardless of whether or not they were born in Europe, have any material connection to “the old country,” speak the local language, or would in fact be safe there). It is a euphemism for “ethnic cleansing,” which is itself already a euphemism that has been normalized and endlessly repeated by leading politicians and mainstream news outlets around the world at least since the war in the former Yugoslavia was ramping up in the early 1990s.

(Source: recherche-nord)

The term “remigration” created an enormous scandal in Germany and elsewhere when it was revealed on January 10, 2024 that “identitarian” figurehead Martin Sellner had talked about it at length in a speech at a secret conference outside Berlin while not only members of the far-right party Alternative for Germany (AfD) listened, but also members of the (ostensibly) center-right Christian Democrats and a cadre of respectable middle class professionals and businesspeople. The news of that conference sparked an unprecedented wave of demonstrations across Germany for several months, and yet, a year to the day after news of the conference broke, AfD co-chair Alice Weidel gave a speech accepting the party’s nomination for chancellor in which she said “I have to tell you quite honestly, if ‘remigration’ is what it is, then it should just be called ‘re-mi-gra-tion!’” That got a huge round of applause, and AfD received the second-largest portion of the vote in the national elections in late February.

It didn’t end there, of course. In May, Reuters broke a story that the US State Department was planning to create an “Office of Remigration” on July 1. As of the publication of this post in late July, 2025, there does not seem to have been any reporting on such an office actually being created, and a search for the term “remigration” on the State Department website produces no results, but the problem remains: the concept has now been recognized as legitimate by the “leader of the free world” and his secretary of state Marco Rubio. And if they should get this office off the ground, “remigration” is set to be repeated on an endless stream of forms, official mastheads, and news articles. So an idea that, if implemented, would necessarily mean mass death for both immigrants and their descendants becomes a little bit less shocking, a little less abhorrent to many people who are not paying close attention or actively pushing back.

This, I believe, is exactly what Victor Klemperer warned us about.

Coda

I’m hoping to crank out an article like this about once a week. And I’m not sure that I’m going to keep this blog in this location, so if you would like to keep up, please do subscribe above.

Lastly, I’d like to formally dedicate my work here to the memory of Victor Klemperer and the legacy of his work. He notes in LTI that it was impossible for him or his book to present the language of the Third Reich in its totality. That is clearly true. It’s a task too big to even contemplate, in part because it neither began nor ended with the Third Reich. So I hope to make a small contribution to illuminating a much larger issue and that I can do Klemperer’s name some justice.

Works cited:

Klemperer, Victor, LTI. Notizbuch eines Philologen. Reclam, Ditzingen, 2018. (All translations are mine.)

Other related works:

Klemperer, Victor, I Will Bear Witness, Volume 1: A Diary of the Nazi Years, 1933-1941. Translated by Martin Chalmers. The Modern Library, New York, 1998. (Available here)

Klemperer, Victor, I Will Bear Witness, Volume 2: A Diary of the Nazi Years, 1942-1945. Translated by Martin Chalmers. The Modern Library, New York, 2001. (Available here)

Klemperer, Victor, Language of the Third Reich: LTI: Lingua Tertii Imperii. Translated by Martin Brady. Bloomsbury, London & New York, 2013. (Available here)