No. “The Great Replacement” isn’t real in any language. Thank you for your attention to this matter!

Unfortunately, however, there are far too many people with very loud voices who keep telling us that it is actually happening, and they are having an impact on both official policy and real-world events in the US, Hungary, Britain, Australia, and elsewhere, so we have to talk about it. In particular we have to talk about why, as a concept, it has been at the heart of such aggressive, even deadly action.

The term was popularized after it was used as the title of a 2011 book that was written in French by French nationalist Renaud Camus; he self-published a second book with the same title the following year. No English translation of the 2011 book has never been published, and there is no widely distributed English translation of the 2012 book either (an abridged translation of the second book was posted on /pol/ at some point before or during 2023, however its circulation appears to be quite limited). So if the term and its explanation have been made available to English-language readers only on a rather restricted basis, why and how was it so readily and widely taken up on the international English-speaking right?

The following is part one of a three-part essay and the first in what will likely be an ongoing series of posts about the deep roots of “replacement ideology,” or anxiety about demographic loss, displacement, or substitution and the associated idea that aggressive measures are needed to rid the national community of outsiders as a matter of collective self-preservation. I’m calling it an ideology because its status among far-right actors goes well beyond a mere slogan or theory, instead forming a complete (if internally contradictory) worldview and a way for reactionary individuals to understand their own relationship with the world around them.

In particular, this post will look at the concept of “the Great Replacement” in terms of what is known as constitutive rhetoric. A classical definition of rhetoric itself would be something like: language that is intended to persuade or change someone else’s mind – to move a person from one camp to another. By contrast, constitutive rhetoric does not seek to change a person’s mind so much as to tell that person that they are already in a particular camp (or more precisely: that they are part of a particular community) and then to induce them to take corresponding action. It’s a useful theory and one that I think will help make the spread of a lot of far-right concepts easier to understand.

Origin of the Term

In his 2012 book titled simply Le Grand Remplacement, Camus doesn’t offer a straightforward definition of what the term means, which may in fact be one reason why it has spread so far: it can be reinterpreted and reapplied to a variety of contexts. Instead, he describes certain personal recollections and then universalizes them, suggesting that his experience is shared by all real French people, and that being French today is defined, at least in part, by sharing his experience.

The main text of the book is transcribed from a talk Camus gave in November 2010 in the small city of Lunel just northeast of Montpelier in the southern department of Hérault. He describes having been there some 15 years earlier and being alarmed by what he saw:

I was in the old villages of Hérault: large, old, round, fortified villages with narrow streets, tightly packed houses leaning one against the other that had already been there for a thousand years – formidable worldly experience for many of them. Some would say that was before there was such a thing as France. Maybe.

In any event, now you might have thought it was after, because in the windows and on the doorsteps of those very old houses and along the very old streets there appeared almost exclusively a population that was new to the area and whose clothing, whose attitude, whose very language did not seem to belong to it, but rather to a different people, a different culture, and a different history.

And in Lunel, which is not a village, there was that same impression of having entered one world without having exited the old one, without having left our country’s streets and plazas with their statues, their churches, and their old familiar landmarks.

How many of us feel the same way day to day? And not only in Hérault, Gard, or Vaucluse; not only in Seine-Saint-Denis, when we can still venture there; not only in Nord or the Pas-de-Calais, but in every part of French territory, along the sidewalks of our cities, in the public transport, on the Paris subways, upon seeing the images or the reality of our schools and our universities. As if within our lifetimes France were in the process of changing its people: you see one, you take a nap, then there is another or several others who seem to belong to different shores, different skies, different architectures, different walls – and who seem to think of themselves that way too. (Camus 2012, 12-3; emphasis original, paragraph breaks added)

The first three paragraphs make essentially three arguments: 1) that the French nation (as distinct from the French nation-state) is very old, possibly more than a thousand years; 2) that French villages that are inextricably bound to the history of the French nation are now overrun by people who do not belong there; and 3) that this phenomenon is not limited to small villages, but also is also occurring in cities, which now appear like a different world – that, at least in the city of Lunel, France is no longer the same country it once was, and these new interlopers are the reason why.

Those paragraphs identify, on the one hand, what Camus regards as intrinsically French and, on the other, who has taken it over. Or, more succinctly: this is France, and that is who has stolen it. (He doesn’t get very specific about the identity of the interlopers in this passage, but here’s a spoiler: he spends a good deal of ink later in the book tearing down a strawman who is, in fact, an ornery, hijab-wearing Muslim woman, juxtaposed with a polite French gentleman. More on these two below.)

He begins this whole passage by describing his personal experience of walking through old villages, but he transitions into a more neutral subject in the second paragraph (“c’était après, aurait-on pu croire”– “you might have thought it was after,” or more literally: “it was after, I/one could believe”) and eliminates any human subject at all in the third paragraph (“c’était cette même impression d’avoir changé de monde” – “there was that same impression of having entered one world,” or, again, more literally: “it was that same impression of having changed worlds”).

The active section here is the last paragraph. There he implies that what he is describing on the basis of his own experience is, in fact, the experience of many if not all the members of his audience right there in Lunel. He even goes so far as to blow that experience up and apply it to “every part of French territory” as he lists a series of locations first in the south near the Mediterranean coast, then in the Paris suburbs, and finally all the way in the north along the Belgian border and the English Channel, implying a broad geographic sweep that takes in the entire country from top to bottom. He is calling on his audience to see themselves in his own experience and to feel a shared sense of loss and alienation upon finding themselves in a changed world without having gone anywhere and certainly without having desired or asked for this.

In short: Camus feels that loss, and he wants his audience to know that his loss is their collective loss too.

How Constitutive Rhetoric Works

The term “constitutive rhetoric” was coined in 1987 by rhetorical studies professor Maurice Charland, although Charland himself traces its practice as far back as the Greek Sophists of the fourth and fifth centuries BCE (Charland 2001, 616). He summarizes how it works as follows:

As a genre, constitutive rhetoric simultaneously presumes and asserts a fundamental collective identity for its audience, offers a narrative that demonstrates that identity, and issues a call to act to affirm that identity. This genre warrants action in the name of that common identity and the principles for which it stands. Constitutive rhetoric is appropriate to foundings, what Hannah Arendt called “founding moments,” but also to social movements and nationalist political campaigns. It arises as a means to collectivization, usually in the face of a threat that is itself presented as alien or other. (616)

In developing his theory, Charland relied heavily on the work of rhetorician Kenneth Burke and Marxist philosopher Louis Althusser to draw out what I would call the dynamics of “that’s me” and “that’s you.”

Burke describes his concept of “identification” or “consubstantiality” (as in: a state of sharing the same substance) in his 1950 study titled A Rhetoric of Motives, where he discusses, for one example, Milton’s poem about the Biblical hero Samson. He notes “the correspondence between Milton’s blindness and Samson’s, or between the poet’s difficulties with his first wife and Delilah’s betrayal of a divine ‘secret’” (Burke, 4). Burke also points out other parallels with Milton’s own life, such as “the Philistines and Dagon implicitly standing for the Royalists, ‘drunk with wine,’ who have regained power in England, while the Israelites stand for the Puritan faction of Cromwell” (5). In Burke’s reading, Milton identified with the protagonist in a well known Biblical story and, in writing his own version, shaped a scenario that highlights their biographical similarities – clearly a “that’s me” dynamic.

Althusser’s idea of “hailing” or “interpellation” is a kind of inversion of that. He does not describe an author writing out an allegory for his own life story, but rather an experience of being identified by someone else (“that’s you”).

[I]deology ‘acts’ or ‘functions’ in such a way that it ‘recruits’ subjects among the individuals (it recruits them all), or ‘transforms’ the individuals into subjects (it transforms them all) by that very precise operation which I have called interpellation or hailing, and which can be imagined along the lines of the most commonplace everyday police (or other) hailing: ‘Hey, you there!’

Assuming that the theoretical scene I have imagined takes place in the street, the hailed individual will turn round. By this mere 180-degree physical conversion, he becomes a subject. Why? Because he has recognized that the hail was ‘really’ addressed to him, and that ‘it was really him who was hailed’ (and not someone else). Experience shows that the practical telecommunication of hailings is such that they hardly ever miss their man: verbal call or whistle, the one hailed always recognizes that it is really him who is being hailed. And yet it is a strange phenomenon, and one which cannot be explained solely by ‘guilt feelings’, despite the large numbers who ‘have something on their consciences’. (Althusser, 264; emphasis original)

What comes out of this hypothetical officer’s mouth as a “that’s you” is then transformed into another “that’s me” in the ears of the person who hears it, and that person, who was previously minding his or her own business, is turned into a subject in a narrative they were previously not a part of – or that they were at least unaware of.

These dynamics also work on a mass scale. Charland illustrates this through the example of the Quebec independence movement in the late 1960s, in which “supporters of Quebec’s political sovereignty addressed and so attempted to call into being a peuple Québécois that would legitimate the constitution of a sovereign Quebec state” (Charland 1987, 134). In order to do so, they “proclaimed the existence of an essence uniting social actors in the province” (emphasis added) in part simply by publicly and repeatedly declaring that “Nous sommes des Québécois” (“We are Québécois”), where most of the French-speaking inhabitants of the province had previously thought of themselves simply as “Canadiens français” (French-Canadians) (134). Movement leaders also utilized “a narrative account of Quebec history in which Québécois were identified with their forebears who explored New France, who suffered under the British conquest, and who struggled to erect the Quebec provincial state apparatus” (135).

And How Exactly Does This Apply to “The Great Replacement”?

In Le Grand Remplacement (2012), Camus similarly addresses a polity as though it already existed even as he is also calling it into being by defining its parameters – who really belongs to it and who doesn’t. Also like the Québécois separatists, he does this by identifying a shared history and articulating “an essence uniting social actors.” The community he is addressing is French, of course, but not just anyone with French citizenship. He illustrates the difference by drawing a contrast between two seemingly irreconcilable figures:

Thus, a veiled woman speaking our language badly, unaware of any of our culture and, even worse, brimming with condemnation and animosity – not to say hatred – for our history and our civilization was perfectly able to claim – and she generally does it a lot, particularly in television studios – to an indigenous French man who has a passion for Romanesque churches, thoughtfulness in his vocabulary and syntax, Montaigne, Jean-Jacques Rousseau, Burgundy wine, and Proust and whose family has lived in the same small valley in Vivarais or Périgord for several generations, where it has witnessed or been subjected to all the twists and turns of our history – she perfectly well claims, and most of the time not in a friendly way:

“I am just as French as you,”

if not “more French,” as I believe I have heard on such occasions.

And legally, if this person has French citizenship, she is completely correct, of course. It would be especially unpleasant to challenge what she has said. And yet it is absurd. More than absurd, it is oppressive. (Camus, 17-8, emphasis original)

Camus also explains at length that “citizenship can only exist on condition that non-citizenship exists” and that, if there is no distinction between citizens and non-citizens, then citizenship means nothing (14-5). And of course doesn’t fail to make it clear that his “veiled woman’s” citizenship is uncertain.

He then goes further and insists that, if she is correct that she is just as French as his “indigenous French man,” then “being French is nothing: it is a mockery, a failed attempt at a joke that turns sad, a stamp from an ink pad on an administrative document” (19). So citizenship, for him, is ultimately contingent not only on having the right documentation, but also on having the right pedigree. What he is telling his audience – both those in attendance in Lunel and those reading his book afterwards – is that “being French” necessarily means denying that certain other people can ever actually be French. People who are French do things like appreciate the right kinds of architecture, read the right books, drink the right kind of wine, and come from the right kinds of families (“that’s you!”); people who are not French wear strange clothing, don’t speak properly, and “don’t seem to belong” in France because of their language or their “attitude” or something.

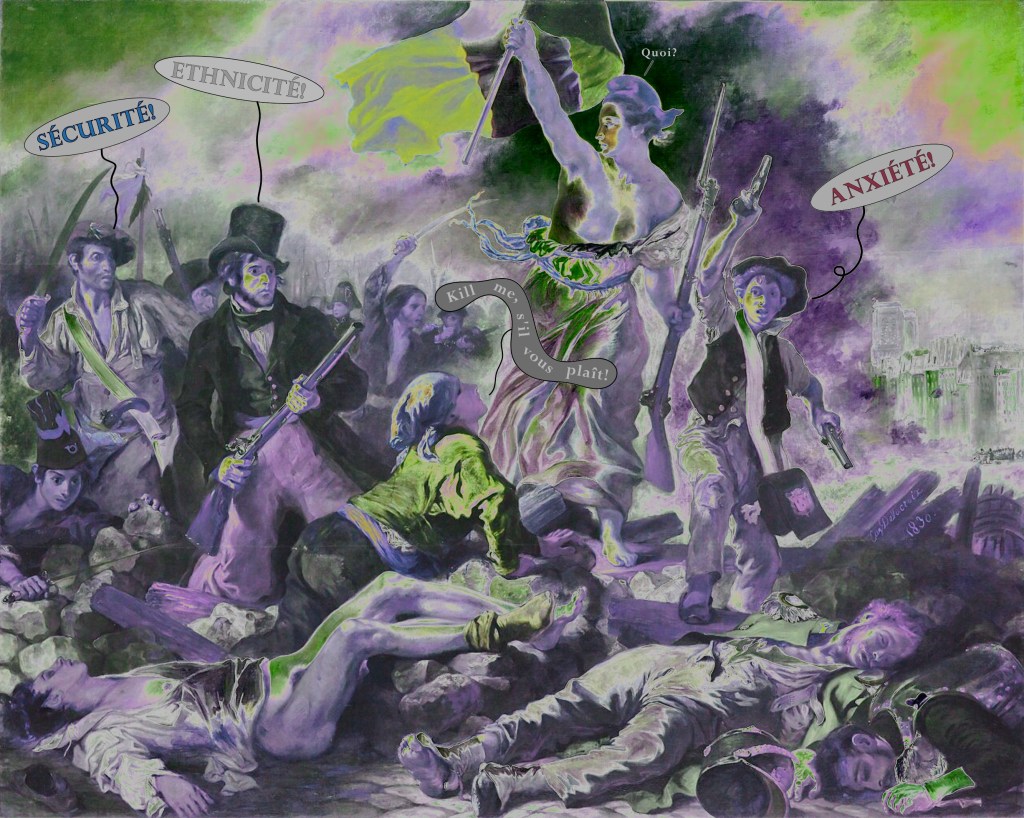

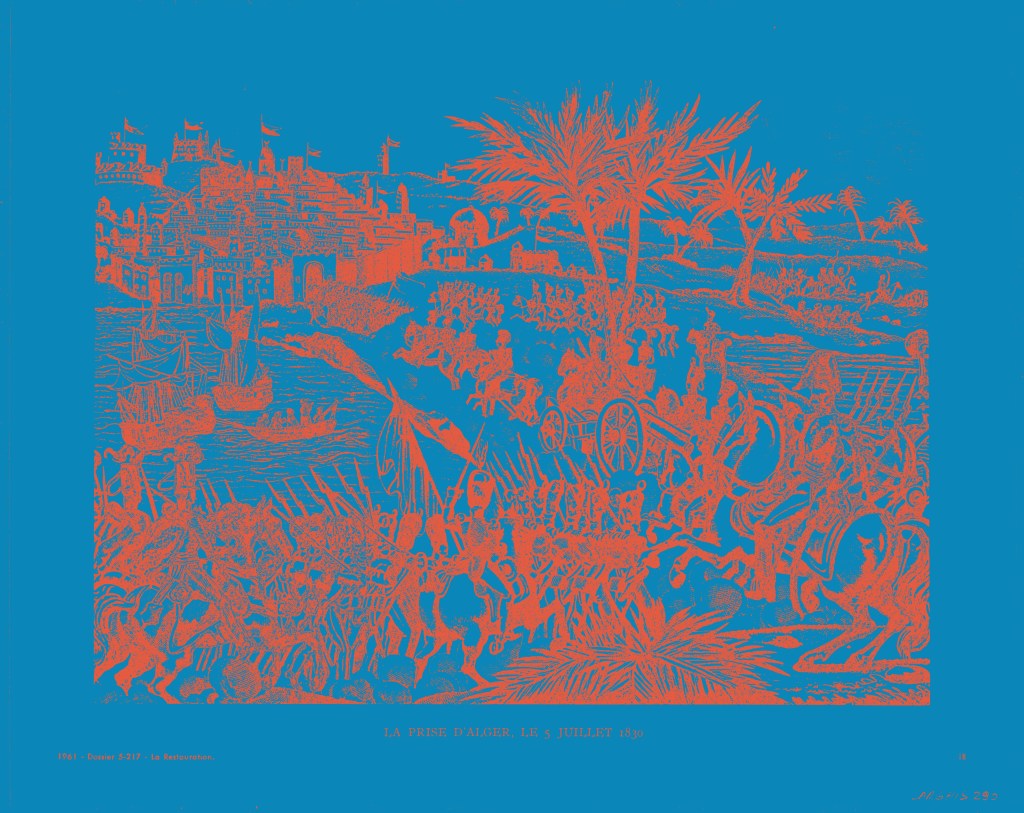

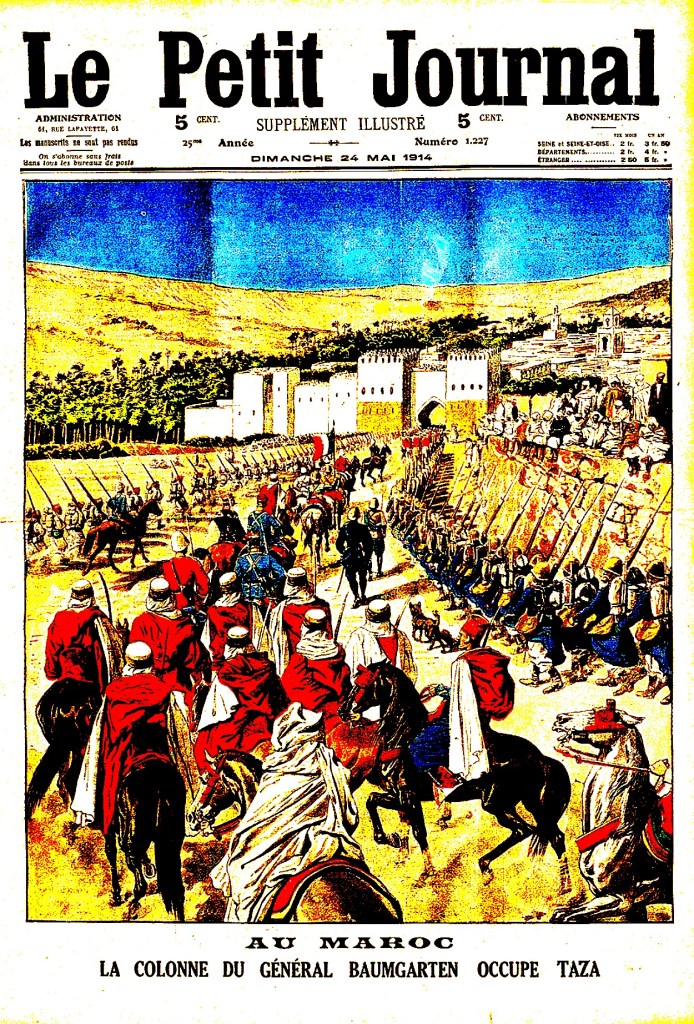

(I’d like to take a moment to point out that, between 1848 and 1962, France regarded Algeria not simply as a colony – as though that wouldn’t have been enough – but as an integral part of France itself. As a result, there were a lot of people in “France” during that period who found themselves in a changed world without having gone anywhere and certainly without having desired or asked for it. These were people, including “veiled women,” who may not have spoken perfect French or known much about French history or culture other than the fact that it was being imposed upon them. And while many nationalists are liable to respond to a point like this by saying something like, ‘Well, Algeria gained its independence fifty years before Camus’s text was written – that’s ancient history!’ I can only respond that, if Camus is going to suggest that buildings that are a thousand years old say something important about what is truly, intrinsically French, then I think we can also accept that events that took place within the past several decades might still resonate in people’s lives today.)

The main problem, in Camus’s eyes, is the presence in France of people who “do not seem to belong to it,” however they themselves are not the only ones at fault. Far-right narratives often distinguish between an external enemy (often a racialized “other,” usually characterized as a rapacious threat to women and/or existing demographics, and frequently described as an “invader”) and an internal enemy (a traitorous figure who allows these “invaders” in or justifies their presence). Camus identifies two groups that could qualify as internal enemies: “the media” and anti-racists. Regarding the media, he writes:

[W]ithin this permanently mutating population in the process of radical, irreversible transformation, there are a lot of foreigners, non-citizens. Admittedly, they do not remain so for long, but to the extent that they officially become French, new ones infinitely appear so that the proportion of non-citizens remains similar and even keeps endlessly increasing, despite the hasty naturalizations. That is the official doctrine – I don’t mean the law, I mean that-which-goes-without-saying in the media, which dictates what the law has to enforce, what the judges have to judge, how reality has to present itself, what events and short news items must mean, even beyond all plausibility… (14)

It is this media apparatus that, he says, produces people who are okay with replacement:

In order for the change of people to occur, the deculturation that proceeds from the disaster of the educational system, of teaching forgetting, of dumbing-down by the media, of the stupefaction industry is indispensable. And the type of man and woman created that way, or rather produced, fabricated, industrially manufactured by television and mass entertainment, that “replaceable man” who receives no rigorous education other than that of dogmatic anti-racism, which is to say the doctrine of his own interchangeability and of interchangeability in general … is exactly what the people responsible for the economic crisis want. (134-5, emphasis original)

He uses the phrase “dogmatic anti-racism” at least 18 times in this 170-page book, and in the process he is willing to invoke a kind of economic populism to make his point. Interesting move for a guy who literally lives in a castle.

Summary

So in comparison with Charland’s model of constitutive rhetoric as it was used by Quebec nationalists, we can say that Camus “simultaneously assumes and asserts a fundamental collective identity” of French “indigeneity” for his audience, partly by naming various things that characterize French people worthy of citizenship and partly by drawing a contrast with people who simply do not belong in France. In particular, he defines the former as threatened with “replacement” by the latter, and in doing so, he defines “indigenous” French people as united in a common struggle for their very survival. In the process, he carves out a basic narrative involving an antagonist, a protagonist (two, in fact: the internal enemy in the form of “the media” and “dogmatic antiracists” and the external enemy in the form of non-indigenous people who can never attain legitimate citizenship), and a conflict between them that is not yet resolved.

But does he call for “action in the name of that common identity and the principles for which it stands”?

In comparison with the Quebec independence activists in the late 1960s, who sought to mobilize voters to participate in a referendum, Camus’s prescription for action is a bit vague. For him, “[t]he center of resistance to what is happening – counter-colonization and Great Replacement – is not demographic growth, nor religion, nor Jean-Marie Le Pen. It is culture and political will – political will in service of culture, and primarily French culture” (65).

Whether intentional or not, this amounts to an endorsement of the same strategy of “metapolitics,” or changing popular sentiment through cultural practices (as opposed to conventional politics), that has been the hallmark of the French New Right since the late 1960s. Camus’s connection with the individuals and groups usually associated with the New Right is rather tenuous, but their ideas have been stewing on the French right since, well, not too long after Algeria got its independence. And whether coincidental or not, Camus’s 2011 book was published just as the nascent “identitarian” movement – which is very much an inheritor of the legacy of the French New Right – was getting off the ground in France. In 2012, that movement emerged on the national political scene with a splashy “occupation” of the roof of a mosque that was under construction in Poitiers. In a press release following the action, the group echoed Camus’s language quite neatly, writing that “[a] people can recover from an economic crisis or a war, but not from the replacement of its population: without French people, France no longer exists. It is a question of survival: that is why every people has the absolute right to choose whether it supports welcoming foreigners and in what proportion.”

This too was a “metapolitical” action.

A Conclusion, Of Sorts

Renaud Camus is by no means the first person to write about demographic “replacement” or articulate “replacement ideology” in French or any other language, so the relationship between his book and the actions or rhetoric of the “identitarians” isn’t strictly one of direct cause and effect: clearly this kind of thinking was in the air on the French far right at the time, and it has remained so ever since. Moreover, the party that Camus founded in 2002 (he was, in fact, ostensibly running for president at the time of his talk in Lunel) has never done particularly well, while numerous “identitarian” leaders have been closely linked over many years now with Marine Le Pen’s National Rally party and, more recently, Éric Zemmour’s even more radical Reconquête. All of this creates the impression that Camus is a bigger far-right rock star outside of France than in it. This may be at least partly due to the fact that, prior to turning to nationalist politics, Camus was already a very successful writer whose best known work included several works of gay erotic fiction. This, conventionally, is not a path to the hearts of the most conservative elements of society.

Still, the specific phrase “the Great Replacement,” which is Camus’s coinage, has clearly implanted itself in the minds of reactionary figures throughout the Western world. It has been uttered by politicians and pundits, invoked in violent demonstrations, and most notoriously it was used as the title of one xenophobic mass murderer’s manifesto – a killer whose actions then inspired several others to follow his lead. This article has looked at what Camus meant by that term and how his argument works as constitutive rhetoric, but it still has not gotten to just how it made the jump to the English-speaking world despite the absence of a widely disseminated translation of Camus’s text.

The next two parts of this essay should help clarify that. Part two will look at the emergence of replacement ideology in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries as cracks were appearing in the edifice of the West’s global colonial project and non-European immigration to the US was being used to justify nativist organizing and action. Part three will address how “replacement” was further taken up in the post-World War II rhetoric of an international right that found itself in the midst of even more rapid shifts in the schema of colonial domination and increasingly unsettled by growing numbers of formerly colonial subjects on the terrain of the colonizers. Stay tuned…

Works cited:

Althusser, Louis, “Ideology and Ideological State Apparatuses (Notes Towards an Investigation),” in: On the Reproduction of Capitalism: Ideology and Ideological State Apparatuses, translated by Ben Brewster, Verso, London & New York, 2014 (1971), 232-72.

Burke, Kenneth, A Rhetoric of Motives, Prentice-Hall, New York, 1953 (1950).

Camus, Renaud, Le Grand Remplacement. Self-published, 2012.

Charland, Maurice, “Constitutive Rhetoric: The Case of the Peuple Québécois,” in: The Quarterly Journal of Speech, Vol. 73, No. 2, May 1987, 133-50.

Charland, Maurice, “Constitutive Rhetoric,” in: Encyclopedia of Rhetoric, Thomas O. Sloane, Ed, Oxford University Press, New York, 2001, 616-19.

[…] A previous post on this site raised the question of how the term “the Great Replacement” came to be used so widely within the English-speaking far right despite the fact that it is derived from French texts that have never been widely circulated (if at all) in English. It also addressed the way that French nationalist Renaud Camus, who coined the term, evocatively explained its meaning using what is known as constitutive rhetoric. […]

[…] first line could have been quoted directly from Renaud Camus, the French nationalist who coined the term “the Great Replacement.” In his book Le Grand Remplacement, Camus writes about visiting French cities and being appalled at […]