[Note: This essay quotes some extreme racist language, including genocidal rhetoric.]

Over the past decade we’ve heard seemingly endless variations on the “Great Replacement” trope from TV personalities, right-wing influencers, politicians, and howling neo-fascists on our streets. It has often been condemned as a conspiracy theory and a not-so-thinly veiled statement of anti-immigrant sentiment, but beyond that, most criticism takes the coinage of the term itself as its starting point, limiting its history to the past decade and a half. What is often left out is that the language of “replacement” has been able to spread so widely in part because replacement rhetoric has been embedded in Western thought for much longer than that.

For our purposes, we can roughly define replacement rhetoric as speech that is intended to provoke opposition to changes that allegedly threaten to alter existing demographic proportions and undermine the numerical advantage of a dominant group. In practical terms, this means opposition to immigration (and to immigrants themselves), regardless of whether or not any evidence exists showing actual harm done to the established population. Rhetoric of this kind can be traced back to at least the mid-nineteenth century and arguably well before that: if it is not necessarily a direct descendant of previously existing rhetoric in favor of “replacing” indigenous populations, then it is at least a close relative.

A previous post on this site raised the question of how the term “the Great Replacement” came to be used so widely within the English-speaking far right despite the fact that it is derived from French texts that have never been widely circulated (if at all) in English. It also addressed the way that French nationalist Renaud Camus, who coined the term, evocatively explained its meaning using what is known as constitutive rhetoric.

The next few posts will look at the long history of elite replacement rhetoric in Western Europe and the United States throughout the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries and how that rhetoric still echoes in the present day. In the meantime, however, the present essay will start by looking at the early part of that period – when Western political and intellectual leaders were so confident in their global power that they openly plotted and in some cases even executed the “replacement” of populations they regarded as their racial subordinates. If it is true that white people often harbor a fear that what whiteness has done to others may one day be done to them, then this background should help us understand a little bit better how and why fear of being “replaced” took hold.

The Descriptive Language of Conquest

To state the obvious: during the process of colonizing most of the planet, the West has not always frowned on demographic “replacement.” The issue is now and always has been: who do they think is replacing whom?

The evolution of the term “plantation” may be worth an entire essay of its own in the future, but for now we can say that, in the “British Isles” in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, it labeled the process of “[trans]planting” overwhelmingly Protestant English and Scottish people onto the island of Ireland in areas that were to be cleared of the Irish-speaking, overwhelmingly Catholic population that already lived there. Oliver Cromwell probably never actually told anyone to go “to hell or Connacht” in so many words, but he nonetheless forced the departure of many local inhabitants and made the lives of those who stayed deeply unpleasant (to say nothing of the people he and his troops killed outright).

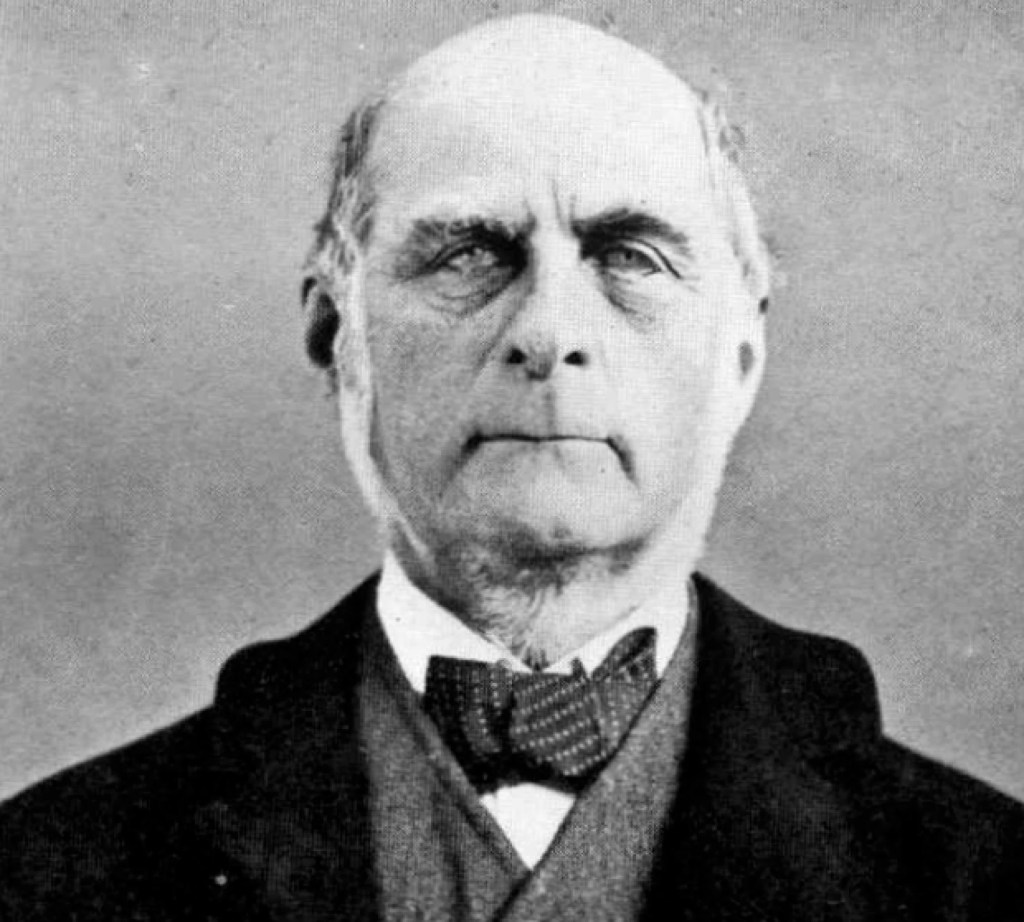

In retrospect, the various “plantations” in Ireland served as a kind of laboratory for figuring out how to make settler colonialism work, allowing Britain to develop its techniques in an adjacent colony before applying them in more remote places. In 1850, some 200 years after Cromwell’s invasion, Scottish surgeon, grave robber, and “race scientist” Robert Knox described a global “replacement” effort in openly genocidal terms:

What a field of extermination lies before the Saxon Celtic and Sarmatian races! The Saxon will not mingle with any dark race, nor will he allow him to hold an acre of land in the country occupied by him; this, at least, is the law of Anglo-Saxon America. The fate, then, of the Mexicans, Peruvians, and Chilians, is in no shape doubtful. Extinction of the race – sure extinction – it is not even denied.

Already, in a few years, we have cleared Van Diemen’s Land [now officially called Tasmania, -ed.] of every human aboriginal; Australia, of course, follows, and New Zealand next; there is no denying the fact, that the Saxon, call him by what name you will, has a perfect horror for his darker brethren. Hence the folly of the war carried on by the philanthropists of Britain against nature. (Knox, 153, original emphasis)

That last sentence is a jab at missionaries and charitable organizations working to make coexistence possible by converting or generally “civilizing” colonized people – as opposed to simply eliminating them altogether. Knox was far from the only apologist for colonial genocide during that era, but his language is worth noting at it is limited to describing the process (in about the most gruesomely trimphalist way imaginable); the usage of “plantation” had shifted, and he does not seem to have access to an established lexicon of “replacement” yet.

The same largely seems to have been the case on the other side of the North Atlantic during this same period. In his Notes on the State of Virginia (1785), Thomas Jefferson wrote approvingly about a plan to “colonize” emancipated Black people, or remove them from US territory and settle them elsewhere, while sending “vessels at the same time to other parts of the world for an equal number of white inhabitants” (Jefferson, 144). A serious discussion of Black colonization would be a major digression here, but suffice to say that the debate about it at the time was more nuanced than it might appear today with just a superficial glance (for context, the Black-led back-to-Africa movement in the US was just starting to coalesce around the time Jefferson was writing his Notes, and its participants were clearly not working primarily to free white people from a supposed Black burden, but rather to free Black people from white racism). The point here is that the author of the Declaration of Independence and future president of the US not only wanted colonization to happen, but he also wanted to compensate for outgoing Black labor with an equivalent number of incoming white people – a rather explicit social engineering plan that amounts to an intent to engage in demographic “replacement.”

In an 1803 letter to future president William Henry Harrison, Jefferson also spelled out “our policy respecting the Indians,” describing a plan by which “our settlements will gradually circumscribe & approach the Indians, & they will in time either incorporate with us as citizens of the US. or remove beyond the Missisipi [sic].” In May 1830, president Andrew Jackson signed the Indian Removal Act into law, and in December of that year, he was able to announce in his State of the Union address that “[i]t gives me pleasure to announce to Congress that the benevolent policy of the Government, steadily pursued for nearly 30 years, in relation to the removal of the Indians beyond the white settlements is approaching to a happy consummation.” These actions, Jackson continues, “will place a dense and civilized population in large tracts of country now occupied by a few savage hunters.”

This positive view of “replacement” wasn’t limited to the English-speaking world, either. In the early nineteenth century, for one example, Colombian economist Pedro Fermín de Vargas echoed Jefferson’s vision of elimination through forced assimilation when he declared that, “[t]o expand our agriculture it would be necessary to hispanicize our Indians. … [I]t would be very desirable that the Indians be extinguished, by miscegenation with the whites, declaring them free of tribute and other charges, and giving them private property in land” (cited in Anderson, 13-4). Here again, the implication is that one population, racially categorized from without, is to be replaced within a given territory by another group, categorized by its own act of racial self-differentiation from the indigenous population.

The texts discussed above are, obviously, clear-cut instances of white men in positions of power ruminating about swapping out Black and Indigenous populations for more white people, however they all needed a lot of words to describe those processes. Jackson, for one, noted that “[t]he tribes which occupied the countries now constituting the Eastern States were annihilated or have melted away to make room for the whites” (as though he, of all people, had not played a decidedly active role in that process). Jefferson first had to address “colonizing” the Black population (itself a shorthand term borrowed from a familiar historical experience for white settlers) and then encouraging white people elsewhere to “migrate hither.” Knox euphemistically describes white settler colonialism (“we have cleared Van Diemen’s Land”) and the “extinction” of Indigenous people. In all of these cases, two processes are described separately: an act of removing (if not outright annihilating) one population and an act of “settling” another. The fact that this is broken down into two parts doesn’t mean much in terms of ideology; the meaning is essentially the same as in the subsequent language of “replacement” (or “substitution,” “supplanting,” etc.). However, it does mean that that language was not yet codified.

Consolidating Terms: It’s Science!

In The Origin of Species (1859), Charles Darwin wrote that, “if several varieties of wheat be sown together and the mixed seed be resown, some of the varieties which best suit the soil or climate, or are naturally the most fertile, will beat the others and so yield more seed, and will consequently in a few years supplant the other varieties” (Darwin, 48). Elsewhere he notes that “the naturalist, in traveling, for instance, from north to south, never fails to be struck by the manner in which successive groups of beings, specifically distinct, though nearly related, replace each other” (264). These are among the numerous passages in the same book describing biological adaptations to environment during processes of natural selection and evolution. The language here is abstract: he is not talking about beings that have discernible personalities, cultures, religion, or historical memory; he is not even writing about individual plants or animals. Instead, he is offering hypothetical generalities that reflect his own research, and the text reads as detached from concerns about morality, theology, politics, or any other human concerns.

Darwin’s book sparked strong, largely hostile reactions when it was first published, but it was not long before some people (scientists and non-scientists alike) began to apply his theories about the adaptability and evolution of distinct species to different “races” of humans. In 1864, English naturalist Alfred R. Wallace, whose prior work had been at least one important inspiration for Darwin’s Origin, published an essay making the following argument:

The intellectual and moral, as well as the physical qualities of the European are superior; the same powers and capacities which have made him rise in a few centuries from the condition of the wandering savage with a scanty and stationary population to his present state of culture and advancement, with a greater average longevity, a greater average strength, and a capacity of more rapid increase, enable him when in contact with the savage man, to conquer in the struggle for existence, and to increase at his expense, just as the more favourable increase at the expense of the less favourable varieties in the animal and vegetable kingdoms, just as the weeds of Europe overrun North America and Australia, extinguishing native productions by the inherent vigour of their organisation, and by their greater capacity for existence and multiplication. (Wallace, clxv)

The relationship with Darwin’s text should be clear here. However, few people were more impressed with Darwin’s work – or more committed to applying it to the emerging pseudoscience of race – than Darwin’s own cousin Sir Francis Galton, who would later invent both the weather map and the term “eugenics.”

Galton’s best known work remains his 1869 book Hereditary Genius, an influential study that just happened to rationalize the brilliance of the people in its author’s own family. It is not that Galton was incapable of empirical research – that is clearly not the case. It is more that he fairly well personifies the culmination of four centuries of justifications for colonialism and the resulting theories of racial hierarchy at a time when the church was rapidly losing ground to the laboratory and the university as a source of explanations for worldly phenomena. His book and its widespread, mostly favorable reception (at least among scientists) can possibly be described as both a cause and an outcome of confirmation bias on a mass scale. And so Galton was able to write a passage like the following in his introduction:

The recent attempts by many European nations to utilize Africa for their own purposes gives immediate and practical interest to inquiries that bear on the transplantation of races. They compel us to face the question as to what races should be politically aided to become thereafter the chief occupiers of that continent. The varieties of Negroes, Bantus, Arab half-breeds, and others who now inhabit Africa are very numerous, and they differ much from one another in their natural qualities. Some of them must be more suitable than others to thrive under that form of moderate civilization which is likely to be introduced into Africa by Europeans, who will enforce justice and order, excite a desire among the natives for comforts and luxuries, and make steady industry, almost a condition of living at all. Such races would spread and displace the others by degrees. Or it may prove that the Negroes, one and all, will fail as completely under the new conditions as they have failed under the old ones, to submit to the needs of a superior civilization to their own; in this case their races, numerous and prolific as they are, will in course of time be supplanted and replaced by their betters. (Galton, xxv-xxvi)

Once and for all, we have a definitively biological rationalization for removing one human population so it can be “supplanted and replaced” by another. (Did I mention that Galton invented the term “eugenics”?) “Supplant” and “replace” are the same verbs used by Darwin in the quotes above, however Darwin used them to describe processes enacted by non-human beings. Galton applies the same language to humans and specifies that some should be “politically aided” in competition against others. In sum, this places him in a kind of rhetorical lineage not only with Darwin, but also with Jefferson – a kind of rhetorical Frankenstein of “Enlightenment”-era ideology.

By 1873, colonial arrogance had reached a point where Galton could confidently write a letter to The Times proposing not only further settler colonialism on other continents or even merely supporting one local population over another, but even inducing emigrants from China to relocate to coastal East Africa under the auspices of the British crown. He called for doing this “in the belief that the Chinese immigrants would not only maintain their position, but that they would multiply and their descendants supplant the inferior Negro race.” Galton felt that this was preferable to colonization (in the conventional sense of the term) by English people because “the countries into which the Anglo-Saxon race can be transfused are restricted to those where the climate is temperate. The Tropics are not for us, to inhabit permanently.”

Similar to Knox before him, Galton’s agenda was unabashedly eliminationist. In arguing for bringing “the Chinaman” to Africa, he starts by writing that “[t]he gain would be immense to the whole civilized world if we were to out-breed and finally displace the negro, as completely as the latter has displaced the aborigines of the West Indies.” Incidentally, his letter offers no opinion about the presence of Black people in the Caribbean, to say nothing of his apparent indifference to the fate of the “aborigines” mentioned here, which, if anything, only heightens the sense that he regards both of these populations (as well as Chinese people) as unworthy of serious consideration as human beings. Instead, he construes them as natural phenomena and only grants them agency to the extent that they are driven by their own, mostly predictable instincts.

Galton’s use of terms like “supplant” and “displace” to describe his vision create the impression that what he foresees is a series of abstracted, globe-spanning chess moves made by an omnipotent authority to serve its own interests. It avoids addressing any of the petty logistics of what would be required, in practice, for a massive social engineering project that would have made Stalin proud. The fact that actual human lives are involved counts for little or nothing, and the casual use of shorthand (but scientific!) verbiage tends to create the impression that mass-scale social engineering of this kind was an accepted part of the colonial repertoire, now rationalized through the wonders of “objective” empirical research.

Galton and Wallace were not the only people to apply evolutionary theory to the study of ostensibly distinct human “races” in the mid- to late nineteenth century, but they were prominent ones, and their scientific bona fides may well have helped that language gain a sense of legitimacy.

Same Language, Different Field: Bureaucracy Edition

Nonetheless, science was not the only field where this kind of language emerged in the nineteenth century. A few decades before even Darwin’s Origins, the bureaucracy of colonialism was already dabbling in talk of “replacement” or, in this case, “substitution.”

In July 1833, while discussing its ongoing conquest of Algiers, a report to the French parliament considered “the violent expulsion of the natives, the … occupation of the territory, and the immediate substitution of a European population for that which now exists” (cited in McDougall, 56). In February 1834, the African Committee of the French National Assembly debated the matter further, specifically with respect to “the nature and number of troops necessary for the occupation of Algiers” (Commission d’Afrique, 207). After extensive discussions about, among other things, the anger that an invasion of French farmers might provoke among the local population on the Metidja plain or how long French farmers in the Bouzaréah massif would tolerate renting the land they were on from its Arab owners – along with some talk about the pragmatics of getting the Arabs to sign that land over (213-4) – one representative finally asked another “if you think the substitution of the European farmer for the Arab farmer is something that will be simple or even possible” (216).

That option was dismissed at the time, however something approaching the same model is more or less what did happen over the course of the nineteenth century along the Mediterranean coast of Algeria (98-100). Moreover, the talk of “substitution” shows that this kind of abstract, objectifying language did not suddenly begin with Wallace or Galton, but rather emerged among colonialism’s advocates over time.

Coda

“Replacement” has become a major component of twenty-first-century neo-fascist rhetoric. If we want to understand how that came to be (and we should, if we want to be able to slow or maybe even reverse its spread), then we need to give serious consideration to its origins. As we have seen, its roots extend back at least as far as the era of global European colonialism (including the establishment and westward expansion of the US) and the early stages of the modern pseudoscience of race.

The people who insist that Europeans and their descendants are being “replaced” today are the same people who, without much in the way of nuance, often describe past Europeans (and their descendants) in heroic terms as builders, inventors, and, of course, conquerors. They are the ones who argue with a straight face that “slavery was good for Black people, actually” and that “colonization brought civilization and culture to the savages.” Given that fascist rhetoric (and that of other closely related authoritarian ideologies) is defined, in part, by a heroic yet somehow also victimized self-presentation, it seems helpful to expose the innate contradiction in that image in order to undermine both parts of it. So what we’ve seen above is a long track record not only of “conquest” but of describing it using the same or similar language that goes into today’s replacement rhetoric, just from the opposite perspective: that of what Renaud Camus might call the “replacists.”

As mentioned at the top, the idea of a “Great Replacement” has been able to take off the way it has because it is a novel way of saying something that has long been embedded in the way history is taught, attitudes are formed, and policies are constructed in Western countries. Knowing that is at least one step toward undoing it.

The next planned essays in this “Roots of Replacement” series will look at both elite and populist anxieties about demographic replacement. These should also finally start to address the gendered implications of replacement rhetoric, although that will also likely require a separate treatment to do it justice.

The present essay took a long time in part because I’ve been traveling a lot, but also because I repeatedly wrote new sections and then decided they should be separate essays unto themselves. With the holidays and more travel coming up, the next sections may take a minute, but with much of it already written, who knows? Stay tuned…

Works Cited:

Anderson, Benedict, Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism. Verso, London & New York, 2006 (1983).

La Commission d’Afrique, Procès-Verbaux et Rapports de la Commission d’Afrique instituée par Ordonnance du Roi du 12 Décembre 1833, L’Imprimerie Royale, Paris, 1834.

Darwin, Charles, The Origin of Species. Literary Classics, Inc., New York, ND [1859].

Galton, Francis, Hereditary Genius: An Inquiry into Its Laws and Consequences. Richard Clay and Sons, Limited, London and Bungay, 1892 (1869).

Jefferson, Thomas, Notes on the State of Virginia, Lilly and Wait, Boston, 1832 (1785).

Knox, Robert, The Races of Men: A Fragment. Lea & Blanchard, Philadelphia, 1850.

McDougall, James, A History of Algeria. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2017.

Wallace, Alfred R., “The Origin of Human Races and the Antiquity of Man deduced from the theory of ‘Natural Selection,’ (1864)” in: Alfred Russel Wallace Classic Writings. Paper 6.