I’ve decided to attempt a regular series of blog posts focused on language and the far right because, on the one hand, I think it might be useful for other people and, on the other hand, giving myself a regular publication schedule will, I think, help me to work through my own thoughts. So here goes.

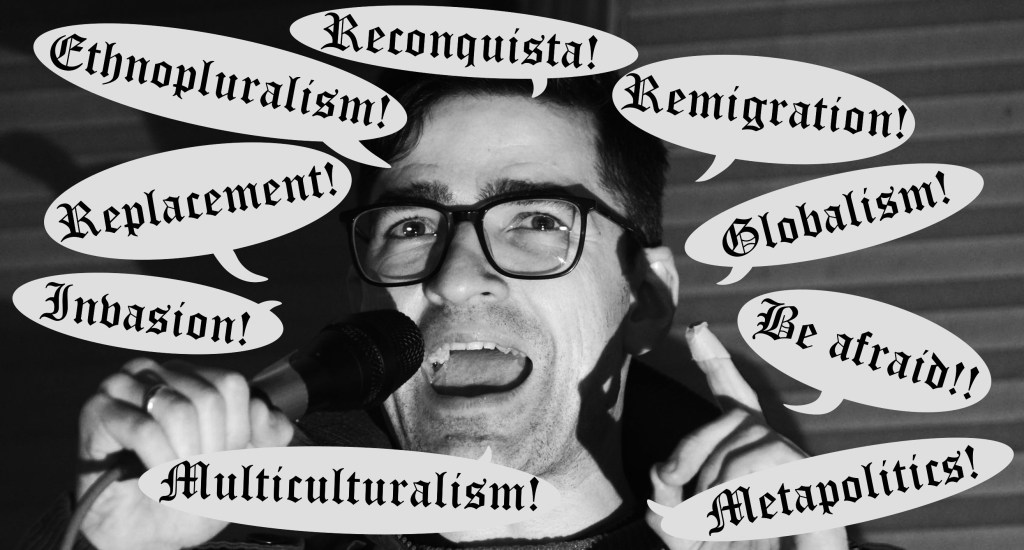

(Adapted from an original photo by Sebastian Willnow / picture alliance / dpa)

On Being a Witness to Fascist Language and Its Consequences

For the first post here, it seems only right and proper to start by discussing the first chapter of LTI, Victor Klemperer’s landmark 1947 book on the Nazi party’s use of language. Klemperer, a German-Jewish philologist who survived the Holocaust in large part (by his own telling) thanks to the support of his “Aryan” Protestant wife, kept a diary throughout the Nazi era. Being a word guy, he naturally kept track of what he called the Lingua Tertii Imperii (Language of the Third Reich, or LTI for short), and the book is based on the portions of his diary that dealt specifically with Nazi language. (The rest of his diaries have been published in various forms over the years, and at least some parts have been translated into English. I haven’t read the other volumes, but I’m told they offer an invaluable glimpse into daily life under Nazi rule, and I encourage people to read them. Scroll to the bottom for details.)

Chapter 1 of LTI addresses the parameters of what he considers to be “the language of the Third Reich,” which amounts to a rather broad spectrum. He begins by pointing to the variety of acronyms the Nazis used, noting that it was partly in response to (and as a parody of) the proliferation of Nazi acronyms that he privately coined the term “LTI” in the first place. Nonetheless, humor is in short supply in his description of its content. He writes

The Third Reich speaks with a dreadful uniformity from all its manifestations and remnants: from the exorbitant pomposity of its opulent buildings and from their ruins, from the soldiers and SA and SS men that it affixed on every kind of poster as idealized types, from its Autobahns and mass graves. All of that is the language of the Third Reich, and of course all of that is discussed in these pages. (Klemperer, 20)

Shortly thereafter, he also mentions “the language of shop windows, posters, brown uniforms, flags, arms extended in Nazi salutes, and pruned Hitler mustaches” (21). Language is never limited exclusively to verbal speech or written text, and that is particularly true of language that is meant to persuade, maintain the ideological orientation of the already persuaded, or remind dissenters of their own subordinate status.

Continue reading