No. “The Great Replacement” isn’t real in any language. Thank you for your attention to this matter!

Unfortunately, however, there are far too many people with very loud voices who keep telling us that it is actually happening, and they are having an impact on both official policy and real-world events in the US, Hungary, Britain, Australia, and elsewhere, so we have to talk about it. In particular we have to talk about why, as a concept, it has been at the heart of such aggressive, even deadly action.

The term was popularized after it was used as the title of a 2011 book that was written in French by French nationalist Renaud Camus; he self-published a second book with the same title the following year. No English translation of the 2011 book has never been published, and there is no widely distributed English translation of the 2012 book either (an abridged translation of the second book was posted on /pol/ at some point before or during 2023, however its circulation appears to be quite limited). So if the term and its explanation have been made available to English-language readers only on a rather restricted basis, why and how was it so readily and widely taken up on the international English-speaking right?

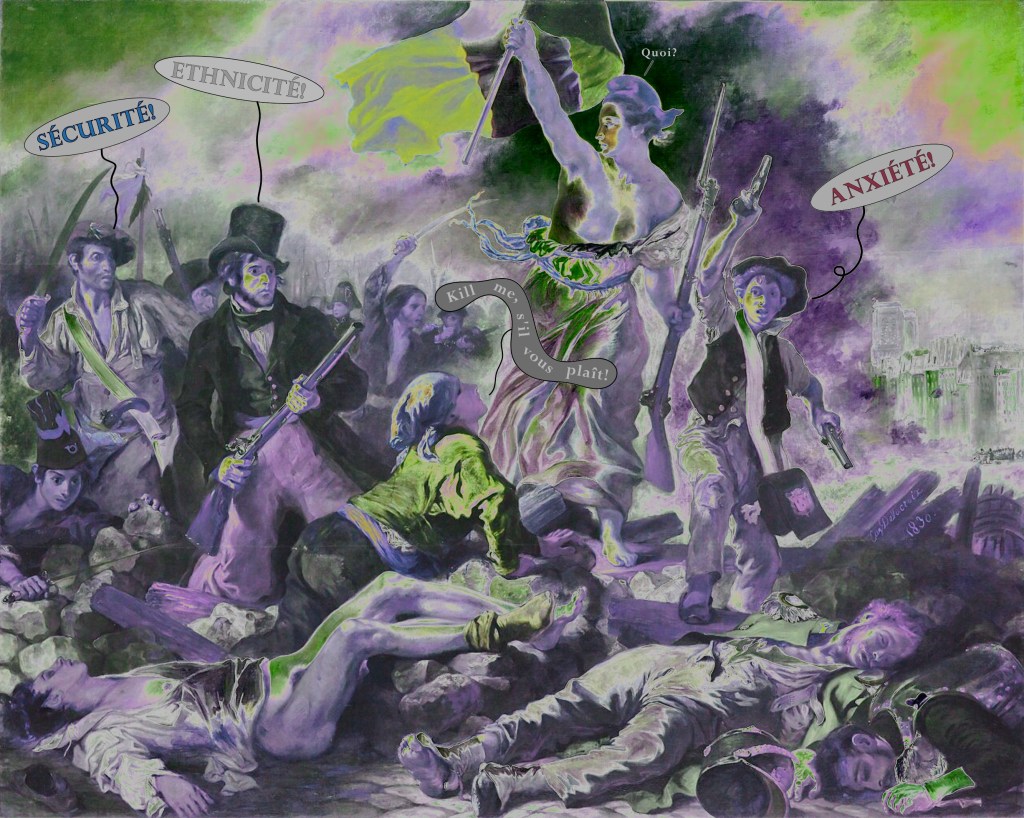

The following is part one of a three-part essay and the first in what will likely be an ongoing series of posts about the deep roots of “replacement ideology,” or anxiety about demographic loss, displacement, or substitution and the associated idea that aggressive measures are needed to rid the national community of outsiders as a matter of collective self-preservation. I’m calling it an ideology because its status among far-right actors goes well beyond a mere slogan or theory, instead forming a complete (if internally contradictory) worldview and a way for reactionary individuals to understand their own relationship with the world around them.

In particular, this post will look at the concept of “the Great Replacement” in terms of what is known as constitutive rhetoric. A classical definition of rhetoric itself would be something like: language that is intended to persuade or change someone else’s mind – to move a person from one camp to another. By contrast, constitutive rhetoric does not seek to change a person’s mind so much as to tell that person that they are already in a particular camp (or more precisely: that they are part of a particular community) and then to induce them to take corresponding action. It’s a useful theory and one that I think will help make the spread of a lot of far-right concepts easier to understand.

Continue reading