[Note: This essay quotes some extreme racist language, including genocidal rhetoric.]

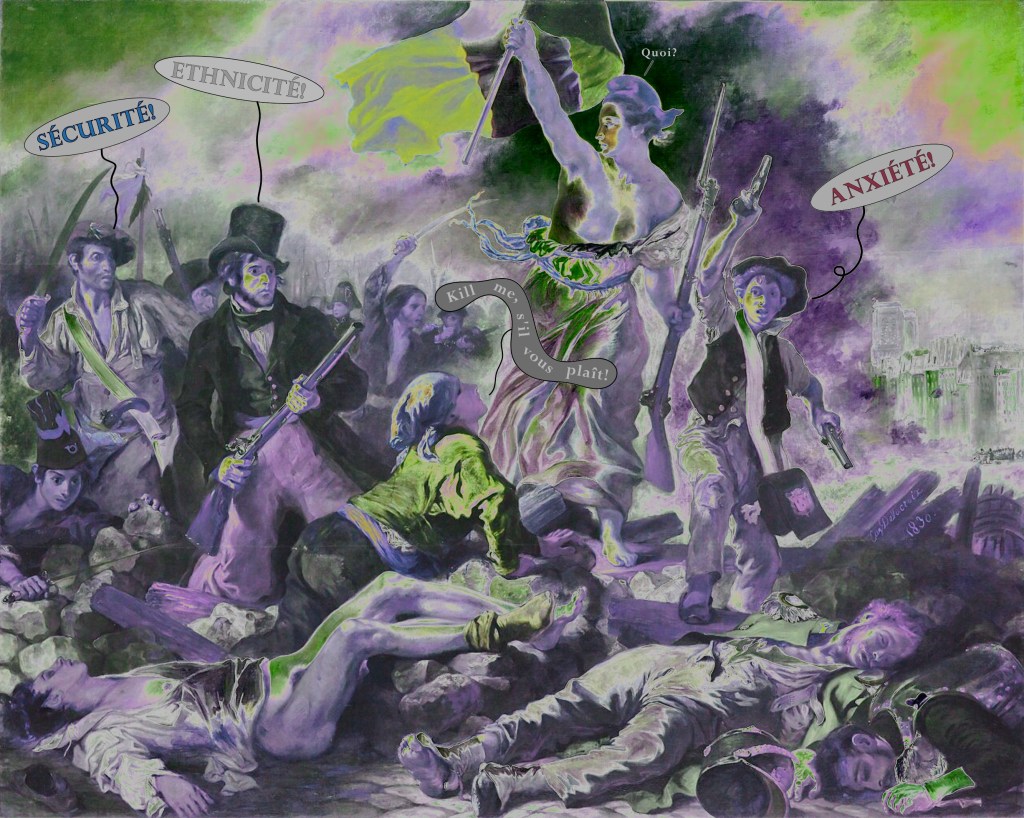

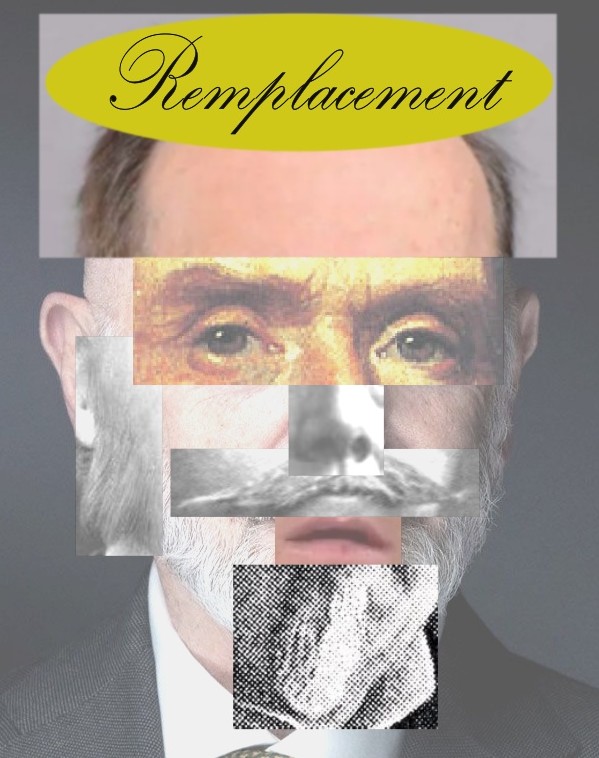

Over the past decade we’ve heard seemingly endless variations on the “Great Replacement” trope from TV personalities, right-wing influencers, politicians, and howling neo-fascists on our streets. It has often been condemned as a conspiracy theory and a not-so-thinly veiled statement of anti-immigrant sentiment, but beyond that, most criticism takes the coinage of the term itself as its starting point, limiting its history to the past decade and a half. What is often left out is that the language of “replacement” has been able to spread so widely in part because replacement rhetoric has been embedded in Western thought for much longer than that.

For our purposes, we can roughly define replacement rhetoric as speech that is intended to provoke opposition to changes that allegedly threaten to alter existing demographic proportions and undermine the numerical advantage of a dominant group. In practical terms, this means opposition to immigration (and to immigrants themselves), regardless of whether or not any evidence exists showing actual harm done to the established population. Rhetoric of this kind can be traced back to at least the mid-nineteenth century and arguably well before that: if it is not necessarily a direct descendant of previously existing rhetoric in favor of “replacing” indigenous populations, then it is at least a close relative.

A previous post on this site raised the question of how the term “the Great Replacement” came to be used so widely within the English-speaking far right despite the fact that it is derived from French texts that have never been widely circulated (if at all) in English. It also addressed the way that French nationalist Renaud Camus, who coined the term, evocatively explained its meaning using what is known as constitutive rhetoric.

The next few posts will look at the long history of elite replacement rhetoric in Western Europe and the United States throughout the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries and how that rhetoric still echoes in the present day. In the meantime, however, the present essay will start by looking at the early part of that period – when Western political and intellectual leaders were so confident in their global power that they openly plotted and in some cases even executed the “replacement” of populations they regarded as their racial subordinates. If it is true that white people often harbor a fear that what whiteness has done to others may one day be done to them, then this background should help us understand a little bit better how and why fear of being “replaced” took hold.

Continue reading